The Website for St George’s Church, Waterlooville and its Parish Magazine St George’s News

Continuing the series of diaries and letters of Alfred Thomas Osmond, relating to his sea voyage from Southampton to Calcutta and his early months in Calcutta, 1852-1853. Alfred Osmond was the son of Rosemary Monk’s Great great great Grandfather William, who was a stonemason at Salisbury Cathedral

Off Point de Galle, Ceylon. Feb.1.1853

My dear Father,

Our long voyage is now approaching its termination. We shall remain here a few hours only to take in a little coal etc. and hope to reach Calcutta in 7 or 8 days. I have kept to my plan of copying my diary as I write it. I fear you will find it not very interesting but there is little to write about except when in port. I have been well and hearty during the whole voyage. During the last few days I have been troubled slightly with what sailors call “prickly heat”. It is merely an eruption on the skin caused by the hot weather – it is a sign of good health – those afflicted with it generally bear the hot climate well. So there is comfort even at this. I have not time to write much more. I thought we should remain at least a day or two & was much surprised on hearing that we shall be clear of the bay before dark. I must therefore take the first opportunity of going ashore to post this. I don’t know exactly about the mails to England so I suppose you will receive a letter from me from Calcutta about a fortnight after you receive this. But you must not be surprised if it is longer – you are never certain about time while at sea.

The natives are coming to me every minute pressing me to buy lace, work boxes inlaid with tortoiseshell & sundry other specimens of their ingenuity. They begin by asking about double what they intend to take. The general rule is to multiply the price they ask by 3 and divide by 5 & you will arrive at something like the real value of the article. Those employed in coaling are working like horses in a state of almost nudity. Mrs Bouchier is sitting with me finishing letters for England. She has just bought some yards of lace of a very handsome pattern for 6d (2 ½ p) a yard. The sailors are all very busy buying rings – supposed to be real opal and gold – but in reality mere glass & brass – manufactured in England. They give old clothes in exchange for these, which the Cingalese take in preference to money. They are calling me to go ashore so I must say good bye. God bless you all & believe me my dear father

Your very affectionate son –

Alfred T Osmond.

My dear Father,

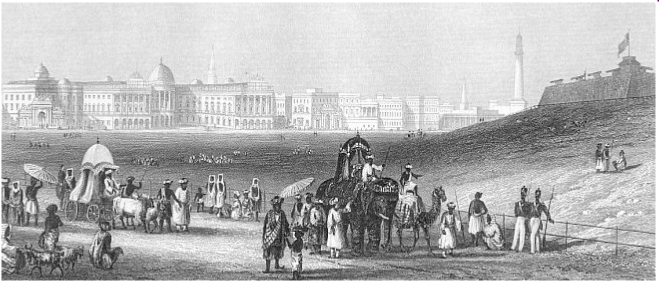

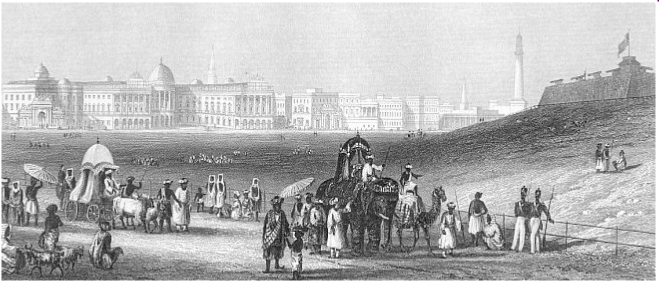

You will be glad to hear that I have reached the “City of Palaces” in safety and am now somewhat settled in my new situation. Before I say anything about the place & people, I will finish my diary of the voyage.

I left off just as we anchored at Galle – just as I was preparing to go ashore, I received an invitation from Mrs Twynham (wife of Capt Twynham, the P&O co. agent here) to join our Captain and Mrs Bouchier at a 2 o’clock tiffin at their house. Mr Brown our 2nd officer accompanied me. We posted our letters first & then proceeded to Capt. T’s. We were followed by a Cingalese, who attached himself to us as soon as we landed & remained with us as our servant the whole time we were ashore. He directed us to Capt. T’s house where we found Capt. and Mrs Bouchier, Mrs T and her 2 daughters. The house is surrounded by a wide verandah, furnished with chairs, tables etc. & here the family sit great part of the day. We spent a couple of hours pleasantly enough – then took leave of our hosts and walked about the town (or village rather) piloted by our Cingalese friend. We entered an hotel, built in the bungalow style (all rooms on the ground floor). Natives followed us everywhere, begging us to purchase rings, chains, card cases & snuff boxes of ivory and tortoiseshell and sundry other trifles. We went aboard again about 5 & at 6 o’clock weighed anchor and proceeded to Calcutta. We took a few passengers here. Two ladies, a gentleman and a little girl – Americans – very thin & bilious-looking people. They spoke English imperfectly. We took a stock of Indian vegetables and fruit at Galle. The bananas or plantain, the pomelow (like an orange but 6 times as large) green oranges, some capital pineapples, bread fruit (which when served up resembles mashed vegetable marrow), yams (like nothing else than thick slices of very stale bread soaked in gravy), sweet potatoes (very like dahlia roots) and sundry others.

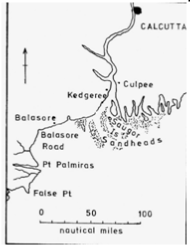

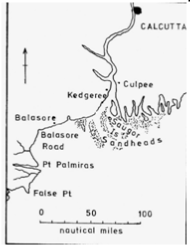

We made a fair passage after leaving Galle. Our American friends were very ill – the ladies did not make their appearance until the last day. The gentleman (Mr Eyoob) and myself became quite intimate. He has lived in Calcutta about 20 years and told me much about Indian life. We reached the Sandheads (the entrance to the Hoogly) early on the morning of Tuesday the 8th February. A master pilot came aboard about 7.30. These master pilots are quite gentlemen – the appointment is worth about £1000 a year. He brought an assistant (called the leadsman) and a Lascar (a sailor from India or SE Asia) servant with him. The navigation of the Hoogly is exceedingly difficult, & in some places dangerous – in consequence of shifting banks of sands. A man cannot become a master pilot until he has served 7 years as a leadsman. I was much pleased with the scenery up the river. It is as pretty as it can be in such a flat country. The width of the stream varies considerably, in some places it is as much as 3 or 4 miles – at Calcutta it does not much exceed a ¼ of a mile. Owing to the sand banks, large vessels are obliged to steer a very winding course – sometimes we were not more than 100yards from the bank. We reached Calcutta about 7 o’clock. It was quite dark so I saw nothing of the place that night. On our passage up we met a large number of vessels towed by steam tugs. Shortly after we arrived at Garden Reach (the P&O compy’s premises), a gentleman came on board enquiring of me. This proved to be Mr Walmsley, Mr Mackintosh’s cousin, who is a partner in the firm. He had a carriage (called a palik-garu) waiting, so I immediately left with him and drove into Calcutta, a distance of about 3 miles, leaving my luggage to be fetched the following day. I was introduced to Mr Jas. Mackintosh & a Mr. Burkinyoung, who is at present an assistant, but who will shortly leave. They are all quite young men, neither of them as much as 30 years of age, & all live together. There is also a brother of Mr M’s about 18 years of age who I believe is to be sent to England shortly. The head clerk, Mr Simmonds, is a married man & lives close by – he is about 50 & has lived in India many years. You will be glad to hear that the business is really an extensive one & that from all I can see & hear, they are wealthy people. A brother of Mr Walmsley is superintending some large contracts a few miles up country. These are all Europeans, but there are 15 or 20 native clerks & draughtsmen. In the timber yard we have at present upwards of 200 carpenters and joiners, & 100 sawyers, & there are some hundreds of bricklayers, plasterers etc employed at different buildings.