I am beginning to feel a little more at home in my new abode, although I am thrown amongst a set of people with whom I can have but little sympathy. Their tastes and pursuits being totally different to mine. My employees are quite young men & each appears to have his own circle of acquaintances, as they are out almost every evening and rarely go together. Of the two, I prefer Mr Walmsley – he is more domestic in his tastes than Mr. M. The latter is always talking of his guns, horses, dogs etc., and boasts of the number of snipe he can shoot in one day. Mr. W. is (or fancies he is) musical. He is a member of the Calcutta Glee Club and wishes me to join, which I think I shall do shortly. It may possibly introduce me to some really musical people.

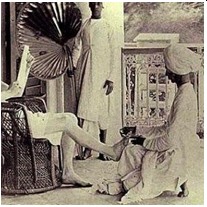

Although I cannot boast much of my progress in the Bengalee language, I am beginning to take my share of the superintendence of the works in progress. At 7 o’clock every morning, a horse and buggy are waiting for me (a buggy, by the way, is a gig with a hood to keep off the sun) and I take a round of some 5 or 6 miles, which, if it is of no other use, gives me an appetite for breakfast at ½ past 8 or 9. By dint of a very little Bengalee, and a great deal of grimace, I sometimes succeed in making the Indians* comprehend my meaning. However there must be a beginning, time will do the rest. I am quite sure that the workmen here may have managed (with proper care) as well as our English labourers. It is the custom here, if a man does not immediately understand you, or if he is slow in obeying an order, to strike or kick him. Mr. Mackintosh tells me it is impossible to get on without it, but I don’t believe it. The poor Indian* never thinks of retaliating or even defending himself from the blows of his white master. The law I believe protects the natives from this ill treatment, but they rarely make complaints, fearful, I suppose of losing their employment. Most of the lower castes, who are employed as mechanics and house servants, have the character of being very lazy, sly and thievish. No doubt this is the case to a very great extent, but I suspect that the English have themselves to thank for it in a great measure. Instead of treating the natives like rational creatures, they have been treated as dogs. I do not yet half understand the various castes amongst them, but they appear to be very absurd distinctions. My servant is a Mussalman, and has no objection to wait on me at table, as well as keep my bedroom in order. A Hindoo would do anything in my bedroom – would wash my feet and put on my stockings, but would not even touch a plate at the dinner table. Along the banks of the river are several “ghauts” or landing places. Every morning you may see hundreds of the natives of both sexes assemble at these ghauts for the purpose of praying and washing themselves in the sacred stream.

I think I mentioned before that Mr. Mackintosh carries on all the branches of the building business – carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, plasterers, painters and glaziers etc. The men work mostly by the piece not by the day. They work in gangs under foremen (called here “mistreys”). These mistreys are the only responsible men – we make contracts with them and they employ as many workmen as they can get. Our joiner mistreys of whom we have about 16, have from 12 to 20 men each. The normal hour of beginning work is 8 o’clock – in some businesses 10 – I was surprised to find they commence so late. Mr. M endeavours to get them at 6 o’clock by giving them a little extra pay, but very few care to do so. The men work almost in a state of nudity – they use no benches, as English carpenters – but squat about the ground like toads, using both hands & feet at their work in a way that would rather astonish our countrymen.

I hope when next I write that Arthur will be here. I hope he will find that his new occupation is as pleasant as he imagines. From what I have seen I think a Purser’s situation is no sinecure though I believe the pay is pretty good.

Pray give my kindest remembrances to all friends – particularly Mr. & Mrs. Fisher, the Miss Saunders and Mr Read & with love to all the dear home party, believe me, my dear William,

Your ever affectionate brother,

Alfred T. Osmond

I hope Sarah’s health is improved. Bessie told me that she was still rather ailing.

(This letter was addressed:- Via Southampton Per Bentinck Wm Osmond Junr. Esq., St. Ann Street, Salisbury, Wilts, England. Prepaid. (The stamp states: Salisbury AP 21.1853)

*The writer uses a term not considered polite today.

Continuing the series of diaries and letters of Alfred Thomas Osmond, relating to his sea voyage from Southampton to Calcutta and his early months in Calcutta, 1852-1853. Alfred Osmond was the son of Rosemary Monk’s Great great great Grandfather William, who was a stonemason at Salisbury Cathedral.

Calcutta, March 3rd 1853

My dear William,

As the mail closes on the 5th and I have a little spare time this evening, I will commence a letter. The overland steamer arrived last night with letters from England of Jany. 20th. I was delighted at receiving a regular budget from Bessie, Arthur, Henry, Charles and Cousin George. Thank all of them for their nice long epistles – I assure you they did me a world of good, even in “sunny India” one is favoured with a fit of blues occasionally.