A Homily preached at Waterlooville on the Feast of Pentecost 2020

I am sure all of you are familiar with the Old Testament story of the Tower of Babel. It is a story set near the beginning of time, after the age of Noah when, according to the biblical account ‘the whole earth had one language and few words.’ The people decide to build a tower which will reach up to the heavens; it’s almost like human beings trying to put themselves in the place of God, with the result that God decides to baffle the peoples by confusing their language so that the builders cannot understand one another.

But what is the story really about?

Well on its surface level we could argue that it is an attempt by an ancient people to explain how a variety of languages existed on the earth, by suggesting that there was originally only one and that the appearance of a multiplicity of languages was the result of a divine act, a divine punishment if you like. It might also be an attempt by the Israelites to make sense of the strange temple towers called ziqqurats which were to be found in the Babylonian empire – particularly if, as some suggest, this story developed during the time that the Israelites were held as exiled captives in Babylon. Indeed it is highly probable that the Tower of Babel itself could be identified with the huge temple tower of Etemenanki, originally constructed almost 2000 years before Christ, but rebuilt and completed by Nebuchadnezzar (the very king who had exiled the Israelites in the 6th century BC). And if this is the case it could be that this story is a kind of warning against the Babylonians who had tried to build a tower right up to heaven, but who would be ultimately frustrated.

But I think the meaning behind the story goes even deeper.

It is a warning against anyone, not least the Israelites, of what might happen if they forsake God. And so it is not surprising that it appears in scripture after the rejection of God by Adam and Eve, and immediately after the story of the flood, both of which led to a divine act of punishment. The actions of humanity have led to the destruction of the unity in creation which God had intended, which is finally symbolised in the confused language or babble that the temple builders are speaking, so that no-one can understand.

Contrast this with the disciples of Jesus on that first Pentecost. These frightened men and women were meeting together in one place in Jerusalem. They were frightened because Jesus, their master had been put to death. They were marked men and women, perhaps they would be next.

And then there came from heaven a sound like the rush of a mighty wind, and it filled the entire house, but not just the house but it also filled each one of them. And tongues of fire appeared among them and descended on each one of them – but this was not like the fire from which God spoke to Moses at Mount Sinai, a fire which no-one could approach for fear of being consumed. This fire was not to burn but to illuminate, not to destroy but to enlighten.

Now Jerusalem was, at this time, full of devout Jews from all over the world. They were there for the Jewish festival of Pentecost or Shavuot. Many of these were Jews whose ancestors had at some time been exiled from their homeland, and settled on foreign soil. Jews who did not speak the native tongue of Israel, but who spoke in a variety of different tongues. The tongues which, in the myth of the Tower of Babel, came into being because human beings turned against God.

And the result of the gift of the Holy Spirit on those disciples on that first Pentecost, symbolised in the wind and the fire, is that these largely uneducated men and women are now able to speak in a multiplicity of languages so that everyone could hear, each in their own native tongue.

Where there had been disunity, now there was unity.

And what they were able to speak of was the power and the love of God.

On this Feast of Shavuot, a spring festival for the Jewish people which also celebrated the giving of the 10 commandments to the Israelites, a new commandment given by Christ himself is reiterated by the spirit filled disciples, the commandment to love.

It is this event, the giving of the Holy Spirit, which marks a new beginning, the birthday of the Church. For those frightened first disciples the gift of the Holy Spirit gave them courage so that a character like Matthew could leave the security of his tax booth and become an evangelist. It meant that an Andrew and a Peter could leave their fishing boats to become fishers of men and women.

It meant the courage to do God’s work, and not their own.

And that is the challenge of Pentecost for each one of us today. The myth of the Tower of Babel has as much to say today as it did all those centuries ago. Human beings still try to construct ‘towers’ or at least to put themselves in the place of a god they no longer believe in.

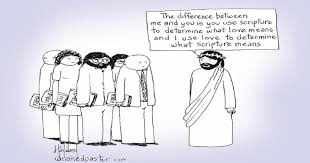

Even within the Church itself, it seems to me, there are people who seem to put themselves in the place of God, deciding what is right and wrong, who is saved and who is damned (usually defined by whether or not they believe exactly the same thing as they do and in the same way) based upon a particular view of scripture. You may have seen a cartoon which appeared on Social Media a couple of days ago which showed Jesus speaking to a group of Christians all of whom aer carrying a Bible, and Jesus says: ‘The difference between me and you is that you use scripture to determine what love means and I use love to determine what scripture means.’ I sometimes think those who use scripture in the way Jesus in the cartoon is critiquing are speaking a different language.

Paul reminds us in our second reading that the Spirit brings with it different gifts and varieties of service. The important point is that all of us are gifted and, as Paul says: ‘To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good.’ Each one of us is called to use the gift that we have been given to build up God’s church. Here at St George’s there is already a sense in which this happens, and this has expanded during the pandemic with people using their unique God-given gifts to help us to function as a church during these difficult times. Hopefully we will continue to explore this as we focus on mission once we return to normality. The important thing for us to remember is that each individual is valued, each gift is important, there should be no sense of superiority or competition. We should act together as one body, committed to using all that we have for the church, the body of Christ, rather like an orchestra where each contribution makes up the whole, and not like a cacophony of different sounds, like in the story of the Tower of Babel. In modern parlance it’s called collaborative ministry.

And above all the gifts that we have should be employed to proclaim the love of God, a love which can unite division, a love which even transcends speech and language.

The proclamation of this love is not easy. It’s not easy because it will involve doing God’s will, and that might not be the same as our own. It’s not easy because of the kind of society that we live in. It’s not easy because it involves complete humility and submission before God – and humility is not the language of the world.

But, like those first frightened disciples, we should take comfort in the promise of God’s gift of the Holy Spirit, to unite, to comfort, to inspire, and to encourage.

Alleluia. Christ is risen. He is risen indeed, Alleluia.

Amen

Fr Dr Colin Lawlor